LARRY ACHIAMPONG’S VISION FOR A NEW PAN AFRICAN IDENTITY

You might be forced to do something that makes you feel uncomfortable, but in order to embrace a new positive identity for Africa and its diaspora, it’s important not to sweep difficult conversations under the carpet. Facing complex issues head-on, multidisciplinary artist Larry Achiampong shows us all how conversation can promote worthwhile change.

In light of recent events, plenty of us would happily turn the clocks back to 2008. Truth is, under the surface little was different – the likes of Trump and Farage have only served to peel back the gloss from a dangerous undercurrent that has always been present.

London-based British-Ghanian artist Larry Achiampong knows it. “It is impossible to not consider the news stories in the West at the moment regarding the rise of Right-Wing Nationalism and Populism”, he posited earlier this year, “but to be honest, there are segments of my practice that have been looking at the effects of these ideals for years. The situation with Trump and Brexit is just a reminder of what we face and what we are increasingly up against.”

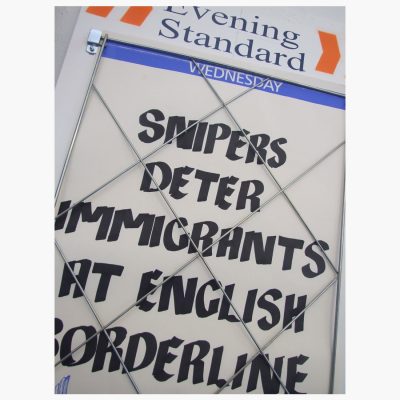

It’s true. Beginning in 2008, his Standard series – in which the artist posed alternative reality futures in the form of newsstand headlines – has been eerily prophetic: ‘Snipers deter immigrants at English borderline’, read one, whilst another bore the chilling, ‘Griffin ‘delighted’ to be new PM’. They might still sound far-fetched to some, but who could’ve then foreseen those post-Brexit hate crimes, the rise and rise of Donald Trump, or the horror in Charlottesville? Perhaps those who have long looked racism in its ugly eyes.

“Just because golliwogs and blackface are not paraded in the way they were in the past, it doesn’t mean the world has thrown that type of mentality to the dust. I think in the UK we are quite guilty of sweeping moments like these under the carpet in the hope that no one will unearth them.” Achiampong is explaining of the sorts of experience that informed his most challenging body of work to date. In Lemme Skool U and Glyth, the artist created quite feasibly the most reductive representation possible of black identity – an emoji-like symbol, simply an entirely black head with bold red lips – and applied it to a series of family portraits.

Taking that work to the nth degree, Larry transposed his ‘cloudface’ character to a performance piece, sitting still in Tate Modern with a physical interpretation of the motif attached to his head; that demeaning golliwog as a real life persona. “To impose a single reductive image that represents ‘blackness’ on to every person represents a way of degrading people, reducing them to ciphers.” It’s chilling stuff, but an important reminder of how those on the sharp edge of racism can feel inside.

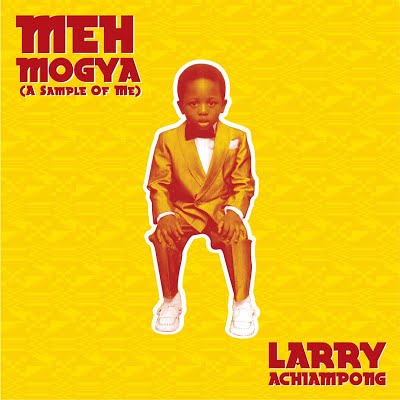

Preoccupied by identity, yes, but Achiampong’s work doesn’t always deal with the sad inevitability of racism. “We are going to demonstrate to the world, to the other nations, that we are prepared to lay our foundation – our own African personality.” The rallying words of President Kwame Nkrumah’s speech to proclaim the independence of Ghana, on 6 March 1957, are laid over spliced samples of Ghana’s euphoric highlife music, the multilayered rhythmic sound that pre-dated Afrobeat, on the multidisciplinary artist’s 2011 album Meh Mogya (My Blood).

A magpie of audio and visual archives, Larry Achiampong’s obsession with identity embraces the cultures he has been exposed to and the cultures that have connected with his own heritage. Imagining how the highlife sound might be interpreted in contemporary times, Meh Mogya (and its follow-up, More Mogya) take the sound and cut it up into bite-sized, beat-heavy nuggets that take the form of the electronic sounds he was exposed to growing up.

“The remix project using highlife records is about trying to bring together popular Ghanaian people’s culture with the kinds of machine-based electronic music – all the house, garage and hip-hop – I’d grown up hearing in East London. I wanted to make those connections between people in different parts of the diaspora.”

Indeed connection is a vital ingredient in the artist’s ongoing work. His latest unfinished project – a science-fiction series based on his character, the Relic Traveller: a Pan-African Unionist from the future whose quest is to collect fragmented data strewn across the planet that relates to lost African history – has seen its first light of day in the form of a flag commission for Somerset House: Pan African Flag for the Relic Travellers’ Alliance, a symbolic path forward for a new diasporic identity.

Representing 54 stars for the 54 African nations – with a symbolic colour palette that includes green to reflect the land; red as a reminder of the struggles that the continent has endured; yellow gold for a new day and prosperity; the black circle an equilibrium in which all states strive together for unity – the flag embodies ascension and a movement toward change, but mostly utilises its prime position on The Strand as a means to stir conversation. “The only rule I set myself”, he says of its making, “was to create something visually engaging enough to start off the question of ‘why?’.”

What does the future of Africa look like? How can we help shape it? With racism and lazy stereotyping boiling over from latency, it’s prime time to extend discussions on Afrofuturism and a new African identity. Race as we know it is a myth that has only existed since European colonialism and chattel slavery; we have the power to reset that notion, but not without people like Larry Achiampong provoking ‘the question of why’.

“From now on, today, we must change our attitudes and our minds. We must realise that from now on we are no longer a colonial but free and independent people”, Kwame Nkrumah continues in his 1957 speech. Six decades have passed, yet attitudes and minds still need shifting – perhaps it’s that tendency to sweep things, things too uncomfortable to face, under the carpet. If there is anything to learn from Achiampong’s work, it is that facing it all head-on, however difficult that may be, is the only way to truly stimulate the conversations that need to take place.

Instead of ignoring Charlottesville and hoping it goes away, turning a blind eye to negligent African clichés, or letting casual belligerence toward migrants go unchecked, call it out. A new and positive Pan-African identity can only truly exist in a world where racism is extinct. Brands and businesses have a voice, and now is the time to use it. Silence is complicity.