ARE FAUX-AUTHENTICITY AND AN OUTDATED NOTION OF AFRICANNESS ENDANGERING THE CONTINENT’S NEW AESTHETIC?

Drop the search term ‘African prints’ into Google Image Search and sit back. The results marry almost exactly to the mental image search your brain had already performed, right? Ubiquitous on the catwalk and in popular culture, synonymous with a hazy definition of Africanness, but most importantly: not African at all.

Flashback to 1846 and the small Dutch city of Helmond: industrialist Pieter Fentener van Vlissingen’s newly-purchased textile factory began creating imitation batik fabric based on traditional designs from Indonesia (then known as the Dutch East Indies – the country had a long history of creating patterned fabrics by applying wax to a cloth, then dying over that wax). The intention? To flood the Indonesian market with cheap, machine-made interpretations of their traditional labour-intensive cloth.

Enlisting a small army of West African slaves and mercenaries to boost their own forces in the then Dutch East Indies, the Dutch inadvertently gave birth to the long-standing history that these fabrics have endured on the continent; the men taking batik back to their home countries, and a taste almost two centuries old being born on West African soil.

Fibreglass mannequins, Dutch wax printed cotton textile, decommissioned antique flint-lock guns, wire, globes, leather and steel baseplates © 2013 Yinka Shonibare MBE

Courtesy the artist and Stephen Friedman Gallery, Photographer: Stephen White © Yinka Shonibare MBE

This faux-authenticity is what led revered British-Nigerian artist Yinka Shonibare MBE to a long career with batik as his muse — tackled by a school tutor for not making ‘authentic African art’, Shonibare was motivated to explore the notion of Africanness, finding the convoluted history of this perceived African fabric the exact metaphor for the identity-minded work that drives him.

“We understand that the war is essentially about power and colonisation. In all of these transactions and trades, there are real human beings involved, and their lives are changed beyond recognition. [These textiles] are a metaphor for the trade routes and identity creation that were a consequence of these complex relations”, the former YBA explains.

It’s not only African artists who’re expected to bang the drum of their continent’s perceived authenticity. Fashion designers, too, face criticism when creating work that doesn’t fit the stereotype. “My aesthetic confused people at first”, admits emerging Kenyan talent, Katungulu Mwendwa. “Some people would even say, ‘is that African? But there’s no print!’ I realised some people have a very narrow definition of Africa which rarely ventures out of heavy, bold print and colour. My response to that idea has always been, “Why do you want to limit my creativity? Are you telling me that because I come from this huge continent – with so many different people — I am only allowed to use wax print when interpreting design?”

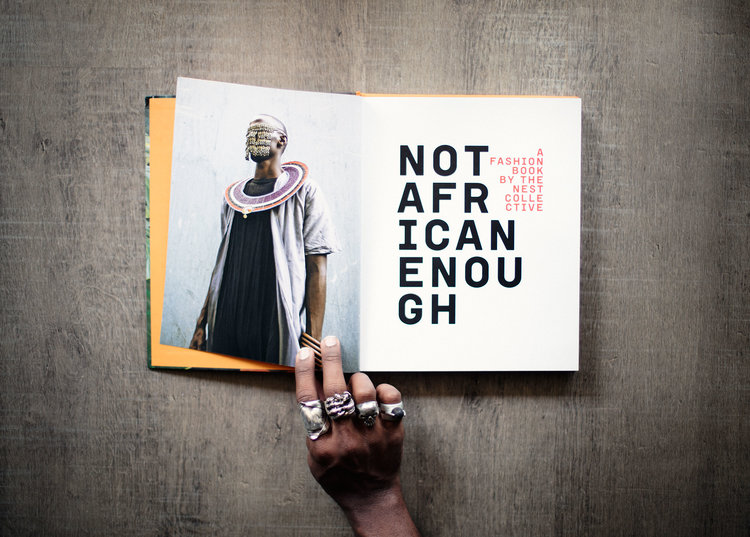

“Not African Enough” is a censure often catapulted at Mwendwa and her fellow pioneering Kenyan creatives – a scolding that has been resolutely rebutted in the shape of Not African Enough – A Fashion Book; a new publication that sees the designer and her contemporaries challenge the narrow expectations of what African design looks like.

Founded in 2012, multidisciplinary ensemble Nest Collective are the creative force behind the book, which explores the work of a series of contemporary fashion designers who are staring down the hackneyed perception of African design. Having worked in film, music, fashion, visual arts, and literature, the collective — under the creative direction of one Sunny Dolat – celebrate the shifting aesthetic of their country and the continent at large; celebrating the talents who operate outside the limited confines of what the world – and Africans – are told it means to dress, talk, think, and be like an African.

“We wanted to challenge the existing narrative of African fashion,” Dolat begins, “which is often examined and analysed using a very singular lens. The designers in the book are people whose voices and vision we deeply admire. For us, their practice opens up new thoughts, creating new visual languages to understand fashion from the continent for the infinity it is, and has always been.”

“We’ve realised”, he admits, “that this is just the beginning of a process. For a while, unpacking diverse African identities has been happening politically or even in academia. But aesthetics, with fashion in particular, has always been given a back seat. The real challenge is how much of our beauty, culture and intention has gone unrecognised and undocumented, and how many knowledge and history gaps we still have left to fill.”

As a new wave of creative talent manages to shake off the shackles of Western compartmentalisation, Not African Enough is a fascinating insight into a pivotal moment in the continent’s cultural aesthetic – but it should also serve as a blueprint for shaping ideas of Africanness moving forward.

Decades since Yinka Shonibare MBE was questioned about his ‘authenticity’, young talents like Katungulu Mwendwa continue to face the same staid line of questioning. If we’re to begin shaping a new future for how African aesthetic looks, it’s high time to leave those notions where they should have been when Shonibare was shaping his practice. What is Africanness? In 2017, it is what African people want to be, and nothing more.