AFRICA’S CREATIVES ARE DOING IT FOR THEMSELVES

Sadly, it will be some years (decades, or more) until Africa and its diaspora shake off lazy pigeonholing at the hands of the West. Inescapably labelled as ‘developing’, the continent’s culture is anything but. Centuries of tradition, art and diverse creativity across 54 countries with distinct personalities: debased by listless stereotypes. It’s true, of those 54 nations, many still struggle with poverty, are involved in perpetual warfare, cope with infrastructure that is decades behind much of the modern world – but the assumption that their creative output is diminished as a result is insulting at best. Unfortunately, outlooks remain tainted by preconceptions, even at the hands of the most liberal of cultural observers.

“Just to have its place in the world of art is good enough for me”, was the response of Ibrahim el-Salahi when asked in 2013 about African modern art’s much-overdue time in the spotlight on the eve of his Tate Modern retrospective. Born in 1930, the modernist was imprisoned in his native Sudan without trial; then the country’s undersecretary for culture, his experience has parallels with African art’s problem at large. “For decades African artists have been working in a vacuum”, he explained to The Guardian, underlining a vital subplot to this story: that Africa itself is ignorant of its own creativity. “In 2011, I went to Algiers for the opening of a new modern art gallery”, el-Salahi continues. “We waited and waited. Finally we were told the event was cancelled because the culture ministers of the African countries didn’t want to come. This is what we’ve put up with.”

The greater acceptance of African contemporary art may be almost a century behind its Western counterparts, but the same can’t be said for the art itself. Derided in the West as being inferior in collectability to traditional African art, considered primitive when compared to its opposite numbers in Europe and the United States, contemporary culture on the continent has been free to form its own singular identity under the shadows afforded to an underdog. Like punk rock, born from a disdain of establishment and fired up on the spirit of resilience, African creativity has embraced DIY ethics; it has dragged itself into the spotlight on its own merits, trodden its own radical path.

Art, design, illustration, music: 54 countries with buoyant creativity. Few contemporary creatives embody the DIY ethics that have typified African culture like Cyrus Kabiru – a Kenyan artist with rebellion at his heart. “My dad told me that if I wouldn’t go to college, to walk out of his house. And that’s what I did. I started my own life”, he recounts of his self-sufficient journey into the art world. Kabiru’s work is free from the conventions of the west and its cultural homogenisation – his unruly eyewear sparkles with all of punk’s youthful aggression and liberation; growing up next to Nairobi’s dump-site, he had dreamt of giving “trash a second chance.”

The Kenyan’s work is inherently African; there is that edge of Afrofuturism in its extraterrestrial leanings, the unavoidable aesthetic of working with found materials. It is, too, deeply singular – resolutely the work of Cyrus Kabiru and no one else. Without that forced homogenisation, artists are free to be informed by their own lives, by their localities and their personal experiences. A self-confessed bad influence at school, traditional education was not for our Cyrus: “if I go to school, I’ll follow teachers. But I have my own art. I have my own way. If I follow a teacher, I’ll follow his way.” Unruly and self-sufficient, it’s an outlook you’ll see time and time again across the continent, an outlook fuelled by that underdog spirit.

Where Kabiru’s choice of material – and, ergo, the nature of his practice – was dictated by a restless artist living hand-to-mouth, the continent’s unique set of problems informs creatives in even its most developed of countries; the lasting linger of racial segregation an inexorable influence on South Africa’s cultural pathfinders. “South Africa has shown me difficult things”, artist Faith47 admits to magazine Instagrafite; “bearing witness to extreme social inequalities and complicated race and gender dynamics is a painful thing. I am very grateful for travelling as much as I do, as I no longer feel that I need to identify with one ‘place’ on the planet. I see the earth as a whole body, and humans as one species, not divided into nations and groups.”

The stigma of Africa has had little effect on the artist, who keeps her real name carefully guarded: Faith47 has played by her own rules and risen to the top of her game with series after series of emotive murals in the world’s street art capitals and beyond. Her work, though, remains profoundly connected to the social issues that have defined her nation — rooted in nature and our subconscious interconnectedness, the South African’s art is tied to the fundamental notion that we are all souls living independently of race, creed or colour.

Fellow Cape Towner Tony Gum exists in a world that could not be more different to Faith47. Where the former operates under the shroud of anonymity, this blogger-turned-rising-art-star riffs on Warhol’s 15 minutes of fame, ascending to international note off the back of viral image and pulling out all the stops to ensure she stays there. Gum’s work is far from shallow: with low-brow culture as her muse, the millennial artist runs the iconography of Vladimir Tretchikoff, Frida Kahlo, Wes Anderson, even Twiggy, through the filter of the West’s view of her continent – Tretchikoff’s Chinese Girl becomes a Ndebele tribeswoman; Black Coca-Cola sees the film and video production student fusing Xhosa heritage with the impudence of pop art’s fascination with mass-marketing; and her Instagram account is a fidgety amalgam of Afro-influence and post-internet art sensibilities.

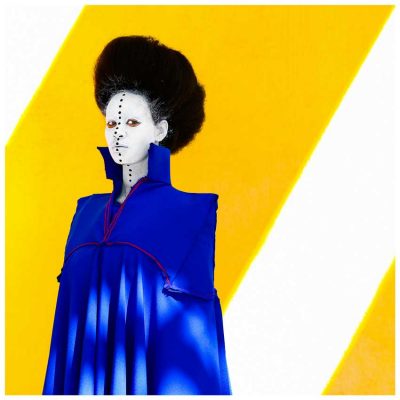

Another African female who enlists herself and her continent’s heritage as key protagonists in her work, Aida Muluneh left Ethiopia at an early age, spending her childhood between Yemen and England before settling in Canada and working as a photojournalist for the Washington Post. A compulsion to return to her homeland was a difficult one to resist, mind, and she returned to Addis Ababa a decade ago. A curator, teacher and founder of one of Africa’s most significant international photography festivals, Muluneh has since swapped commercial photography for art, and her practice is in real ascendency; African tradition deeply ingrained in each image she makes. Bouncing through surrealism, pop, and expressionism, Aida’s cinematic scenes are loud and symbolic – a world away from the austere monochrome that defined her photojournalism.

However bold Aida Muluneh’s work may be, there is still a vulnerability in her psyche that goes back to growing up in a place as complicated as Africa. “I remember when I was a teenager, I was so ashamed to tell people that I was Ethiopian that I wished I was South African”, she confesses. “The stigma of the ‘starving Ethiopian’ made it impossible for me to have any kind of pride in being Ethiopian.” A cruel irony. For, to the casual Western outsider, Muluneh is African wherever she may have grown up – and Africa is the land of animals and of war and of famine. Fifty-four unique nations. The largest continent on earth. One universal stereotype.

“There is not one Africa; there are many Africas”, asserts the publisher of black culture magazine Afrolicious, Ann Daramola. “Wherever you see the word Africa, simply replace it with the term ’The Africas’ and watch how the myth unravels. ’The Africas’ preserves the continental identity while also critiquing the monolith myth by producing in the readers’ and writers’ minds an image of multiples: multiple countries, multiple languages, multiple peoples, multiple problems, multiple solutions.” Is it that simple? Have I been a part of the problem over the course of the last 1,300 or so words? Yes and no. No and yes.

Africa has an individual set of problems. A continent seen as a whole. An often negative whole. And, yes, any meditation that draws on its tradition and heritage, its culture and contemporary creativity, is symptomatic of a broader quandary – but it is this Africa, this individual set of problems, that has shaped the singular careers of the handful of artists mentioned herein. For every one of these creatives, there are thousands more – each utilising their own resistance to lazy pigeonholing, each forming their own identity under the shadows afforded to underdogs. Raw creativity doesn’t crave mainstream acceptance, and Africa’s bold DIY creatives have turned the lack of it to their advantage. The continent may continue to grapple with its own issues, but its creatives are doing just fine.