#AFRICATOO

Tweeting with the hashtag that has changed the landscape of female empowerment, writer Faustina Anyanwu reveals the extent of workplace harassment in the Nigerian medical industry. “Frustrating for female nurses”, she laments, “having to choose between their job and satisfying doctor’s sexual advances.” Medical directors, doctors, and sometimes patients, too, regularly harass and abuse nurses, claims Anyanwu, in what is a sad, but predictable revelation. Although women in the West have recently been spurred on to speak out en masse, revelations like this have been regrettably fewer in Africa, many of its nations weighed down by cultures that hamper the process of getting such issues out in the open.

According to The World Bank’s 2016 report, “Poverty in a Rising Africa”, an astonishing 40 per cent of African women in partnerships have experienced domestic violence. More alarming is the reported acceptance of such abuse – 51 per cent saying they believe beatings to be justified if they have gone out without telling their husband, refused to have sex, or even overcooked food. If women are better educated, or live in a richer country or region, then their tolerance toward violence is considerably less; yet despite that Africa’s upper-middle-income and high-income countries have higher rates of domestic violence than poorer countries. In cultures like this, just talking about harassment in the workplace remains a difficult proposition.

“It is almost impossible – in fact, unimaginable – for a woman to report such cases”, Anyanwu explained to the Thomson Reuters Foundation; “culturally, the woman is ostracised and will not be married.” Ninety-five per cent Muslim, it’s widely expected for Senegalese women to remain virgins until marriage. “We don’t talk about these things”, said Dakar-based musician Daba Makourejah, who posted to her public Facebook page an account of harassment; “there is a taboo here against everything to do with sexuality.” The global significance of #MeToo, though, has begun to pierce the bubble that surrounds less progressive cultures.

“There are a lot of African women who are strong and fighting for their rights, and it is important that their voice is also heard”

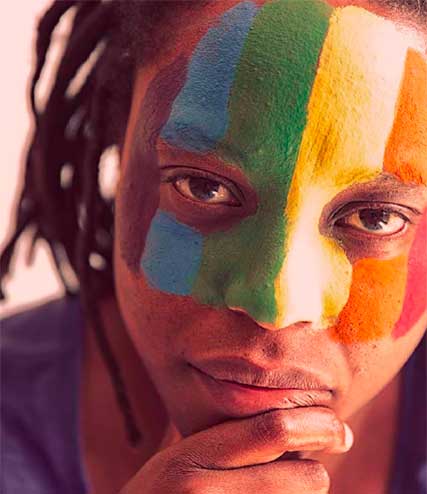

Ato Malinda

#MeToo is not without its own issues, the globalisation of social media clouding the very personal struggles behind each woman. “I think that it is important to have feminism within your own context”, explains artist Ato Malinda, whose powerful work is frequently grounded in African feminism and sexuality. “Feminism is a lot of things, and obviously the sort of narrative – and the debilitating factor of feminism – is the overarching notion that it is promoted by Western white women. I think that is just not the case. There are a lot of African women who are strong and fighting for their rights, and it is important that their voice is also heard.”

There is a concern, too, that more explicitly African issues such as female genital mutilation (FGM) are overlooked by the campaign. “FGM is a form of sexual abuse, but yet again we’ve been left out”, activist Leyla Hussein explains. Often justified for religious or cultural regions, campaigners say a desire to control female sexuality is at the heart of this horrifying practice. “FGM is a way of controlling our sexuality, our bodies, our thoughts”, adds Hibo Wardere, a British activist cut as a child in Somalia. “It’s a way to make you feel like nothing but a commodity that belongs to a man… That’s what we’re all fighting against.”

Concerns aside, there is no doubting the significance of the #MeToo movement. Sent viral by Alyssa Milano in the wake of sexual misconduct allegations against Harvey Weinstein, “me too” is a phrase coined by American civil rights activist, Tarana Burke, who is known to have first used it back in 2006. Named alongside others in a group dubbed The Silence Breakers as Time’s Person of the Year 2017, Burke stands among a growing global populace who have found emancipation in speaking out. “There’s something really empowering about standing up for what’s right“, says former Uber engineer, Susan Fowler, who is wholly comfortable with her new-found reputation as a whistle-blower. “It’s a badge of honour.”

Though there was predictability in the shaming of Hollywood’s sleazy power players, the movement quickly swept through industry after industry – Silicon Valley to The White House; hospitals to hotels. Named among Time’s Silence Breakers, the Plaza Hotel Plaintiffs – a group of seven women who filed a harassment suit against the hotel — represent a tip of the iceberg for a travel industry yet to be widely shaken by the movement; though casino mogul Steve Wynn’s recent resignation is sure to urge a rethink of the outdated ‘what happens in Vegas, stays in Vegas’ trope. From the needless sexualisation of lounge bars and pool parties, right down to ensuring a safer, more equal workplace for all, there is no doubt that the movement will reshape travel over the coming weeks, months, and years.

As the movement continues apace, it’s critical that the essence of its meaning – not its celebrity sheen – is what defines it. #MeToo is empowerment in a hashtag, but we can only feel empowered if we first address awkward matters.

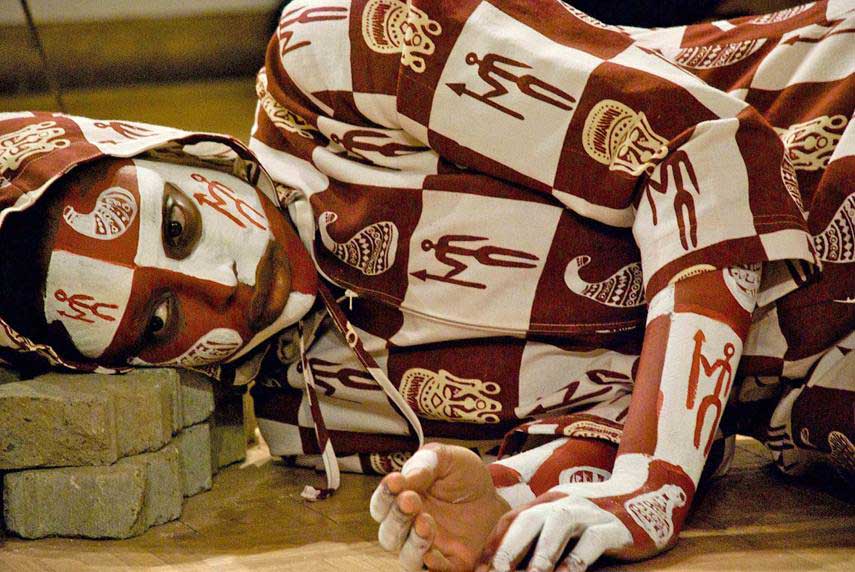

“It is time for people to feel uncomfortable”, states controversial South African artist and activist Lady Skollie, “and for people to ask themselves very hard questions about how they relate to women; how they treat them; how they talk to them.” Skollie, real name Laura Windvoge, is an African artist making major waves on the international art scene – her brash, hyper-sexualised approach is both potent and divisive, but impossible to ignore. Through irreverence and humour, Windvoge forces consideration of issues that too often go unnoticed.

“It is time for people to feel uncomfortable, and or people to ask themselves very hard questions about how they relate to women; how they treat them; how they talk to them”

Lady Skollie

“People don’t always want to listen if you are being serious”, she reveals. “They would rather not listen to preaching and they don’t want to hear about rape stats, HIV stats, and so on. I think in some ways I’m pretty funny, so I use humour as a way of unwrapping serious issues in a palatable way, so that people will actually start thinking about change.” It’s a reminder that in many African nations, the issues behind #MeToo are sometimes hard to bring out in the open, a reminder that change need be the result of many cumulative factors. Social media has the ability to rapidly unite people from around the world, but if that message fails to connect for local reasons, no amount of universal reach will enact change.

Which brings us back to the cultural shift needed for heightened awareness to convert to a positive impact. As Ato Malinda points out, it is important to remember that harassment knows no creed nor colour; “we have to keep our focus on people of different class and race and gender”, reaffirms Tarana Burke. In the West, #MeToo has revealed that the overt sexism of workplaces pre-1990s – topless calendars and leering bosses – had only been swept under the carpet, its latent threat never truly addressed. For many African nations, male privilege remains shockingly out in the open. “We can’t walk anywhere in Johannesburg”, Laura Windvogel tells Public Radio International (PRI) in a 2017 interview. “As a woman, if you were walking somewhere and you got raped, people would be like, ‘babe, no offence, but it was your fault.’ It’s like, ‘you know you shouldn’t be walking.’ And that’s the thing: it’s so easy; everything we do is monitored and controlled by our fear of men here.”

Which is not to say that African women are weaker because of the cultural norms against them: quite the contrary. “Myth and stereotype blind the world to the reality of what African women are accomplishing”, wrote Nobel Prize laureate Leymah Gbowee in a 2014 op-ed for the LA Times, celebrating the strength and resilience of Nigerian women who stood up to Boko Haram following the abduction of hundreds of schoolgirls. “For years, Western media had no idea what had happened.” Going on to lament the lack of international reporting of Christian and Muslim women uniting in protest during the darkest days of Liberia’s 14-year civil war, the prominent peace activist continues: “It is time for the world to put away the image of African women as victims and see them as the everyday heroes they are.”

In Ethiopia, a 14-year-old who attends a junior-secondary school in Addis Ababa embodies that everyday hero. A member of the school gender club initiated by UNICEF, she acted after a friend confided in her that a teacher was sexually abusing her. “It was scary for us”, she tells UNICEF Ethiopia, “because if he saw us together he may know what we were up to. We were all so afraid of the teacher.” Inspired by the #MeToo movement, the emphatic bravery of young African women has resulted in direct change: the teacher was ultimately jailed for his actions. Empowered by what they have achieved, the youngsters symbolise the resilience Leymah Gbowee talks of. “Now that the teacher is out”, adds one of the victims, “no one else would dare to do that to us. We feel stronger and more confident to take action.”

“It is time for the world to put away the image of African women as victims and see them as the everyday heroes they are”

Leymah Gbowee

And this is the potency of #MeToo: its power in numbers; its ability to reinforce the notion that you are not alone. “For a long time”, begins Nigerian author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, talking about the movement in an interview with AFP, “women in many parts of the world felt that they couldn’t talk about these things because they would not be believed and because there would be many consequences for them. I know that in Nigeria young women follow the news, and I also know that suddenly some young women started to talk about their own experiences.”

Going on to tell the story of a woman who talked candidly on Facebook about her experience of harassment at the hands of a medical school professor, Adichie extols the wind of change #MeToo has brought with it: “to talk about it openly and to name the man who was a professor… That is very unusual. It’s just one story, but for me it is symbolic of what this all movement has brought about.” The feminist figurehead confirms Leymah Gbowee’s belief in the strength of African women, adding that, whilst they might not use the language of Western feminism, the way they live their lives says all that needs to be said.

“Don’t fear the shifting tide of female empowerment: embrace it”

The most important takeaway from this is that great exposure can truly bring great change. Don’t fear the shifting tide of female empowerment: embrace it. These issues might be awkward to broach, but openness and inclusivity is changing lives the world over. Hotels can, and should, do more to encourage and protect female travellers (regardless of location); gratuitous sexualisation – no matter how ingrained in culture, or ubiquitous – needs to be readdressed; relics from the past need to be razed. Change can be painful – nobody said it was going to be easy – but we can learn valuable lessons from those who’ve had the courage to speak out. Be as unafraid and formidable as Africa’s everyday heroes. Be empowered.

[This article was published in Beyond: Empowered, We Are Africa’s print magazine, in May 2018.]