BUILDING UTOPIA: BODYS ISEK KINGELEZ

Was Congolese artist Bodys Isek Kingelez the greatest architect who never was?

Existing on the fringes of the art world, Kingelez — who passed away last March, aged 67 — exemplified the rare freedom with which Africans approach creativity; unshackled from the inhibitions of conformity that is bred in the culture of the West. Bodys Isek Kingelez was a designer, an architect, a builder, an urban planner capable of conceiving entire cities; yet his works remained uninhabitable. (It is worth noting his highest skyscrapers only just surpassed two metres in height.)

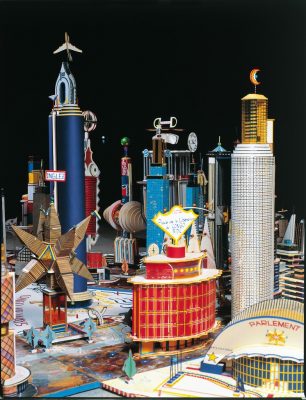

For all that Kingelez was, his greatest asset was imagination — here was an architect who existed solely on an intellectual plain. Like visionary Lebbeus Woods before him, this was a creative unafraid to ask: ‘what if?’ Where Woods’s fanciful drawings leaned towards the realms of science fiction, Kingelez dealt in a surreal extension of non-fictitious Modernism; the Congolese artist using paper and found objects to craft quixotic models that sought to take the limits of architecture to wild new heights.

Objekt/ Object, © Bodys Isek Kingelez,

Courtesy C.A.A.C. – The Pigozzi Collection, Geneva

Having made Congo’s chaotic capital Kinshasa his home in 1970, Bodys lived among its aesthetic and political anarchy until his death — surely serving as an inspiration for his poetically utopian visions. Beginning work in the 1960s at the city’s national museum, Kingelez’s meticulous practice was born from an early career restoring traditional African masks; his intricate work switching from very old to very new after losing that job in the early 1970s. Here his ‘extrêmes maquettes’ (extreme models) began to take shape — miniature buildings informed by a rise in radical architecture that was reflecting the rebirth of African nations in a post-colonial era.

The futuristic feel of African Modernism, and the bizarro unconformity of cosmic Soviet architecture, had clearly had an affect on the young dreamer, and his singular sculptural style was born; model buildings that would progress to entire cities in later years, all crafted with utopian ideals at heart. Imagining public buildings, urban dwellings, and sports venues, Kingelez’s creations were joined by parks, waterways, and avenues in 1994, when the artist realised Kimbembele Ihunga, his first model metropolis. As his artistic ambitions moved up a gear, so did his desire to inspire: ‘I created these cities so there would be lasting peace, justice and universal freedom,’ Bodys said of his work. ‘They will function like small secular states with their own political structure, and will not need policemen or an army.’

© 2010-2016 The Contemporary African Art Collection

Born into the Belgian Congo, Bodys Isek Kingelez’s homeland had been recognised as Zaire since 1960, and amid violent civil war in 1997 it would become the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Persistent unrest was informing the artist’s practice, his models becoming more elaborate, more impressive, more concrete as blueprints for better futures: ‘thanks to my deep hope for a happy tomorrow,’ Kingelez proclaimed in a manifesto, ‘I strive to better my quality, and the better becomes the wonderful.’

And the art world was following this progress. Centre Georges Pompidou was the first major international institution to sit up and take note of Kingelez’s work — the sculptor taking part in a group show at the Parisian gallery in 1989 — and by the end of the 1990s, the Congolese had been exhibited at New York’s Museum of Modern Art, Berlin’s Haus der Kulturen der Welt, and London’s Serpentine and Saatchi galleries; to name but four. The former restorer had arrived and, as the century turned, his colossal and complex visions of utopian metropolises had become hot property; reputed art publisher Hatje Cantz put out a monograph in 2001, and curators the world over were using his work as a means to demonstrate Africa’s shifting cultural tide.

Indeed, Kingelez was one of many artists determined to recast the stereotypes of his continent, the sneering Western outlook of safaris and witchdoctors — his work, too, a deliberation on the chaotic building projects that have blighted the Third World. Fanciful and overflowing with positivity, yes, but Bodys addressed important topics through his extravagant visions; battling negativity to the end with an ardent optimism his creations symbolised. In the mind of Bodys Isek Kingelez, utopia already existed.